A city is dependent upon its design; a well-designed city does not just come across as aesthetically pleasing but becomes the fiber of its citizens’ lives. Though we often give little thought to urban dynamics they shape everything about us. They shape our economies and our health, our jobs and friends: our happiness. Though it can be difficult to notice, Calabasas is a broken city, one designed solely for cars rather than its own residents. This must change.

In 2020, Walk Scores published its walkability rankings for U.S. cities. Out of a potential score of 100, New York held an impressive 88.3, while Calabasas held an abysmal 22. By metrics of bike infrastructure, Calabasas ranked even worse at 15 for having “minimal bike infrastructure”. Such car-centrism hurts Calabasas, and it’s only through its wealthy residents that the local government stays afloat, because car-centrism is expensive.

Roads on average last only 18-25 years, and they cost a whopping $100 thousand—$1 million per mile. Though statistics are not available for Calabasas, Los Angeles County has over 7100 Lane miles, at a bare minimum that is $710 million every 25 years, and far more likely around $3.55 billion every 20 years. This is for Los Angeles County—for all of California it takes billions of dollars every year, and the road infrastructure in urgent need of repair across the state will cost $135 billion. That would be 43.4% of the state budget on basic road maintenance, showing how incredibly unsustainable this system is.

Aside from city expenses, there is the issue of personal expenses. In the U.S., the average cost of owning a car is $894 a month, the second largest household expense for most, and this is simply for the ability to travel. Not to mention the health benefits of walking and cycling compared to sitting in a metal vehicle, sometimes for hours and stuck in endless miserable traffic. Such a high cost is detrimental to thousands in Calabasas, as the poverty rate has risen from 6.7% to 9.5% and inflation tightens budgets, the need to own a car becomes ruinous.

Even by taking public transportation, which is appallingly sparse in the U.S., you still save hundreds of dollars a month. In London, which is more expensive than any other major city, it costs $191.54 a month to use the bus for all transportation., For moving into inner London and using the underground, it can cost $430 a month which is still half that of owning a car.

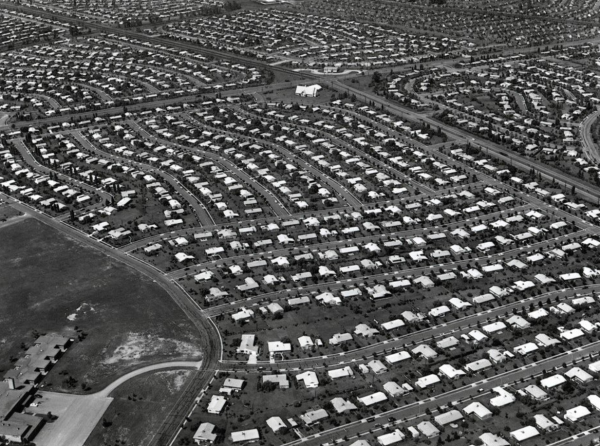

The most glaring issue of Calabasas’s urban environment is the sheer disconnect. Ever since White Flight in the 50s and 60s, with mostly white people moving into suburbs, the idea of privacy and isolation has been ingrained into Americans. In 1946, the first Levittown was constructed by William J Levitt, creating a sparse landscape with homes spanning the entire landscape, and yet it feels empty. It is massive but small; it can feel endless but it is so rigid and simple that it appears boring. Your entire life is boiled down to your home, workplace and places where you get necessities—a design that is so flawed that suburbs now host higher poverty than cities and far more prevalent mental health problems. Levittown aimed for utopia, but resembled dystopia.

It is everything inherently inhuman about people. We are not perfect or neat or simple, we are not distant and isolated and we do not like driving despite the American Dream of the freedom to go anywhere trying to convince us we do, or at least we do not like it as much as we do methods of traveling that sadly many Americans never experience.

Imagine leaving your home on the third floor of a relatively small but cozy apartment and walking down the street into a lively road with musicians playing and shops dotted on the pavement. Cars are nowhere to be seen, and you sit down in a pleasant coffeehouse, watching the people and the nature, the detail of the buildings and the pigeons that flock to a woman giving bread.

In what you just read, I could be describing Amsterdam. I could be describing Vienna, I could even be describing London loud and congested as it is. This is a reality more common than many think, even in the U.S. the human tendency to be more attracted to detail and organization is a fact of how people live in cities. American cities like New York and Philadelphia triumph at many of these aspects that make a great city, and though they are behind their European counterparts, Calabasas isn’t even in the race.

Jane Jacobs, a hero to many urban planners, pinpointed this in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. She spoke of how the dense North End of Boston, long considered a slum and denied loans constantly, was the amalgamation of great urban design. Though it was considered poor, crime was drastically lower than in the rest of Boston. It additionally had a low mortality rate and little disease. Though it was once a slum, she describes revisiting it and finding it a beautiful place with the refurbishments all funded by the citizens of the struggling North End.

The low crime rate she attributed to the verdant sense of community, to the shops on every street, to the bustling people acting as observers against crime, to the butcher who would come out of his store when a man would act suspiciously outside—it was a community, one that was mostly made up of immigrants, being dubbed Boston’s Little Italy today.

Calabasas lacks such a community. Most meaningful bonds are made in the workplace or school. Places to sit and work or write in public are rare but where they are, such as Barnes & Noble, is a good demonstration of how a detailed and lively environment with more people attracts others.

Though Calabasas is making little progress, what progress it is making is welcome. This year Rick Caruso, billionaire and CEO of real estate company Caruso, announced that the Commons would receive a significant makeover, the most important of which is the demolition of the Regency theater to make way for new stores and 119 new apartments, with most stores at a walking distance from your home. A sort of town square and beautiful decor like this could be Calabasas’s walkable neighborhood, depending on the specifics of the unreleased timeline.

The massive need for housing in Calabasas holds the potential to reshape its Urban environment. As of last year, it has met a mere 5% of its state-mandated goal of affordable housing. If construction were permitted it could make Calabasas more dense, walkable and affordable—it could reshape Calabasas in the right ways. It could also provide it with far more economically productive downtowns. Other cities such as Barcelona suggest that more walkable downtowns and neighborhoods fuel economic activity by potentially 30%. A more economically productive downtown would give a boost to the city budget, which could fund more housing.

A city is brittle; it is organized chaos which in itself is paradoxical but somehow we achieve it. City planning pretends to be a science but in its current state more closely resembles astrology in its blind devotion to a brutalist, car-centered and inhuman design. A city built upon such principles of control and organization leaks, breaks and accumulates issues. They are weaker than a human-oriented city which acts more like an organism that heals and naturally prevents disease and crime. Calabasas is failing at this. Crime, especially violent crime, and poverty are on the rise. These are issues that urban design can prevent. The cracks will only grow until the city undergoes a transformation—a rebirth of Calabasas.